As the founder of New York Said, I typically share stories that celebrate the vibrant culture and diverse voices of New York City. However, my conversation with Antino Crowley-Kamenwati demanded a different approach. The depth and sensitivity of his experiences, combined with the potential impact his story could have on others facing similar challenges, led me to present this material as an personal evolution study rather than our usual cultural profile article.

This format allows us to examine these critical issues with the gravity they deserve while maintaining respect for Antino’s experiences. Our goal is not to sensationalize trauma but to understand it, learn from it, and hopefully help others who may be silently carrying similar burdens. By approaching his story with careful attention and deeper understanding, we aim to contribute meaningfully to the broader conversation about trauma, healing, and transformation, particularly within communities where these discussions are often suppressed.

Listen to Our Conversation

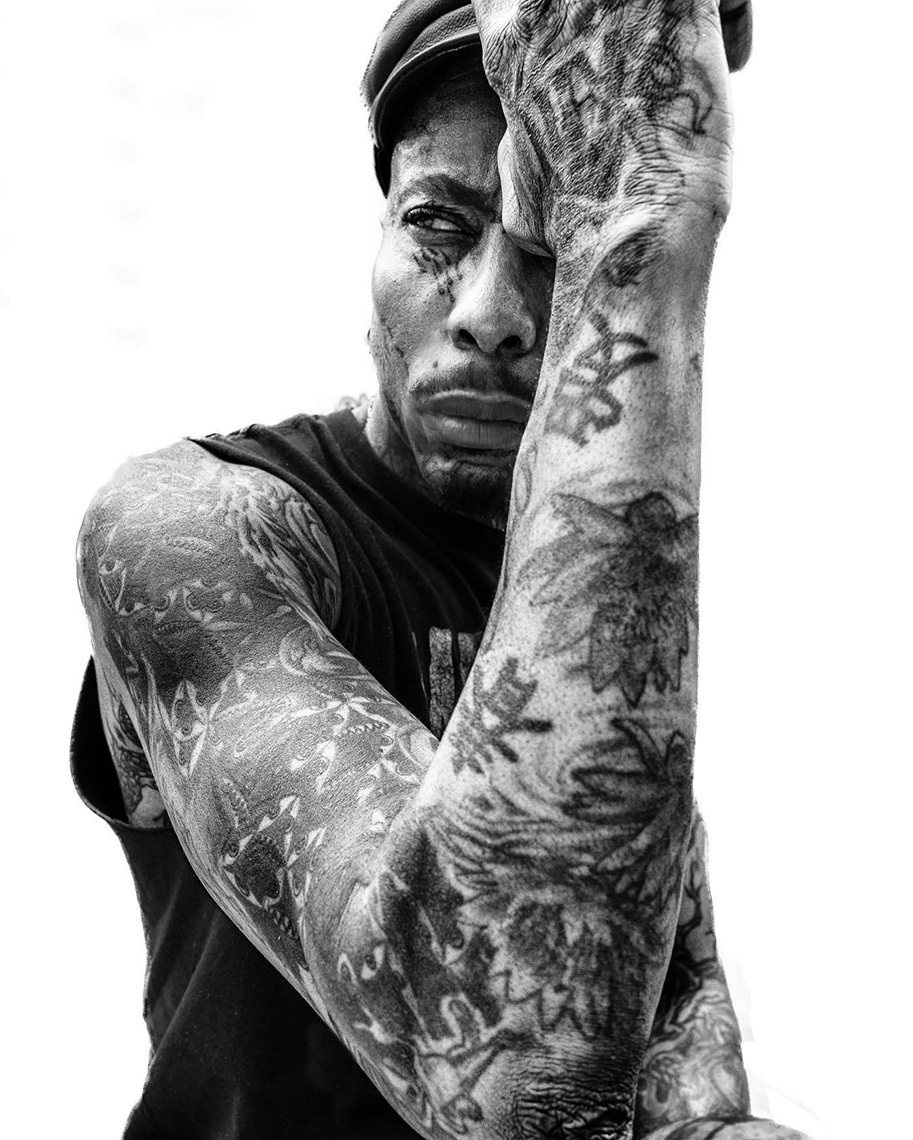

Antino Crowley-Kamenwati, Photography by ALEX KOROLKOVAS

An Analysis of Survival, Self-Discovery, and Artistic Expression

Introduction

The first time I met Antino Crowley-Kamenwati, I didn’t know his story. At a Jerkface art opening, he was working the door—cool, composed, and magnetic. What struck me most was his style: tattoos stretching over his face and neck, piercings that caught the light, and a braided black jacket that seemed architecturally sculpted rather than sewn. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. But in true New York fashion, I simply nodded, and continued into the gallery. Later, at the end of the night, I asked if he’d sit down for a conversation for New York Said. He agreed.

Our plan to meet in Washington Square Park was ruined by freezing rain, so we relocated to Café Reggio. The cold didn’t matter; neither did the noise of rain hitting the tin roof of their outdoor dining shed where we finally sat. What mattered was the rawness of what followed: a 90-minute reckoning with a life shaped by relentless pain, unimaginable betrayal, and a refusal to surrender.

This isn’t a story of redemption tied up with a bow. It’s a story of survival. It’s harsh, unrelenting, and above all, real.

Background and Early Life

Antino grew up in Atlanta’s Ben Hill section during the 1980s, in what appeared to be a successful Black upper-middle-class household. His grandfather, a minister and businessman, owned multiple dry cleaning businesses and convenience stores. This outward success masked a household environment where profound trauma would shape Antino’s early development.

“I grew up around women,” he explains, describing a childhood spent with his mother, grandmother, and aunts. This environment, while nurturing in some ways, became complicated by rigid social expectations about masculinity. His interests in art, comic books, and Wonder Woman drew criticism, particularly from his stepfather who attempted to “butch me up.”

The Impact of Early Trauma

From ages three to ten, Crowley-Kamenwati endured sexual abuse from three different relatives. The significance of this abuse cannot be understated – it occurred during critical developmental years and within a cultural context that made disclosure particularly difficult.

“In the black community, elders are really promoted as somebody you listen to,” he explains. “Anybody older than you is an elder… you’re supposed to listen to them and do what they say.”

This early trauma shaped his relationship with his own darkness. As a child, he retreated into his mind, finding safety in isolation – a coping mechanism that would later fuel both his criminal activities and his art. “My head has always been a safe space for me,” he explains. “Even to this day, if I’m dealing with something, I shut everybody out.”

His pain manifested in other ways too. He started stealing at age four – a little Snoopy telephone book from a Hallmark store. By his teens, he was boosting clothes from malls. In his early twenties, he graduated to fraud and check schemes. “I have an extensive criminal background,” he says. “That’s why I play convicts and police interrogation scenes very, very well.”

But perhaps most chilling is the rage he carries – contained, but always present. “If you touch me, I black out,” he explains. “And it is – I become something else, and I don’t like it, and it’s scary because I don’t know what I’m capable of.” He recounts a fight with an ex who made the mistake of hitting him: “Fight moved to the bathroom. I picked him up and slammed him into the glass shower doors. They shattered, glass everywhere. I was pummeling him. I bit off a chunk of his ear, bro.”

This power dynamic, combined with threats and social pressure, created a perfect storm of silence and continued abuse. The impact manifested in several ways:

- Behavioral Changes:

- Beginning of theft behavior at age four

- Development of kleptomania

- Progressive escalation to more serious criminal activity

- Psychological Impact:

- Retreat into mental isolation

- Development of protective mechanisms

- Formation of complex relationship with rage

- Identity Formation:

- Complicated relationship with sexuality

- Struggles with self-worth

- Development of dual nature (“dark mind, light heart”)

Paths to Healing

Crowley-Kamenwati’s journey toward healing involves several key elements:

- Artistic Expression:

- Training at Maggie Flanagan’s conservatory

- Development of acting career

- Use of performance as catharsis

- Body Modification as Therapy: “Every time I was sinking into a depression, I would go get tatted, because I would replace that mental pain with the sting of the needle.”

- Channeling Rage: His ability to access and control rage through acting provides a constructive outlet for processing trauma.

But perhaps most remarkable about Crowley-Kamenwati isn’t the darkness he’s endured, but the light he’s maintained through it all. “My soul is gentle. My soul is full of light,” he insists. “I love people, I love humanity, I love nature.”

This duality manifests in his career as an actor, where his distinctive appearance and raw emotional depths have landed him roles films like “Clean,” and a recurring role on “Law & Order: Organized Crime.” His ability to access rage on camera comes from a place of profound understanding – both of darkness and the importance of containing it.

“Acting is a cathartic way for me to release my demons,” he explains. “Otherwise, I’d be back in prison or an insane asylum.”

The tattoos that have become his signature weren’t just aesthetic choices – they served as a form of therapy. “Every time I was sinking into a depression, I would go get tatted,” he reveals. “I would replace that mental pain with the sting of the needle.”

Among his most striking pieces is the phrase “false idol” inked right on his eyelids – a reminder both to himself and others about the dangers of worship in an age of ubiquitous celebrity. It’s a philosophy that seems to permeate his worldview: authentic, unvarnished truth over comfortable illusions.

The Transformation of Trauma

Perhaps most significant is how Crowley-Kamenwati has transformed his experiences into tools for both personal healing and broader social impact:

- Professional Success: His understanding of darkness and pain has enhanced his ability to portray complex characters in shows like “Law & Order: SVU” and “Gotham.”

- Social Contribution: He is developing a documentary series about sexual abuse of Black men, working to break the silence around this rarely discussed topic.

- Personal Philosophy: Despite his experiences, he maintains a fundamentally optimistic worldview: “I love people, I love humanity, I love nature.”

Implications for Understanding Trauma and Resilience

Crowley-Kamenwati’s story offers several key insights:

- The importance of finding constructive outlets for processing trauma

- The potential for transforming personal pain into artistic expression

- The role of body modification in reclaiming personal autonomy

- The impact of cultural and social factors on trauma recovery

- The possibility of maintaining empathy and optimism despite severe trauma

Now in his mid-forties, Crowley-Kamenwati has found a measure of peace with his darkness. He’s developing a documentary series about sexual abuse of black men, breaking the silence around a topic too often buried in shame. “Out of all groups of men, our toxic masculinity and our fragile male egos are the worst,” he explains, “because we’ve had to be more manly than other groups of men because of slavery and because of how white men have always kept us at the bottom.”

Despite everything – or perhaps because of it – he remains an unexpected optimist. “I love people, I love humanity,” he insists. His hardest learned lesson? “Just because you were good to someone, they’re not obligated to be good back to you.” Yet he continues to give, to help, to nurture – keeping his light heart even while acknowledging his dark mind.

As our conversation wraps and the rain pounds harder on the cold tin roof above us, I’m struck by how Crowley-Kamenwati embodies the complexity of trauma, resilience, and transformation. He carries his darkness not as a burden but as a tool, his pain not as a wound but as wisdom. In a city of millions, his story stands as testament to the raw, unvarnished truth that sometimes the deepest waters run the darkest – and that within that darkness, light persists.

Conclusion

For those working with trauma survivors or experiencing trauma themselves, Crowley-Kamenwati’s journey offers hope while acknowledging the complexity of healing. It suggests that the goal isn’t to erase darkness but to find ways to channel it constructively while nurturing one’s capacity for light.

Recommendations for Further Research

Future studies might examine:

- The role of body modification in trauma recovery

- The intersection of racial identity and trauma processing

- The use of performance arts in healing from childhood sexual abuse

- The impact of cultural masculinity norms on trauma disclosure and recovery

Support Resources

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual abuse, trauma, or is struggling with mental health issues, please know that help is available:

- National Sexual Assault Hotline: 1-800-656-4673 Available 24/7, confidential support

- RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network): WEBSITE

- The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI): 1-800-950-6264 24/7 crisis counseling and support

- LGBT National Help Center: 1-888-843-4564 Peer support, community connections, and resource referrals

- Black Mental Health Alliance: WEBSITE Culturally competent mental health resources and support

- Male Survivor: WEBSITE Support specifically for male survivors of sexual trauma

- The Trevor Project: 1-866-488-7386 Crisis intervention and suicide prevention for LGBTQ+ youth

These organizations offer confidential support, counseling referrals, and resources. You don’t have to carry your burden alone. Whether you’re ready to speak now or just need information for the future, these resources are here for you.

Remember: Your trauma does not define you. Your past experiences are part of your story, but they don’t have to determine your future. As Antino’s journey shows us, transformation is possible, and healing, while complex, is within reach.

Note: This study is based on a single in-depth interview conducted in New York City in 2024. While offering valuable insights, further research would be needed to generalize these findings to broader populations.